From mollusks to mountaintops: Working with federal agencies to make strides in conservation science

July 15, 2021

On a remote corner of campus, in tanks and constructed ponds bubbling with fresh water, an unusual life cycle is taking place.

At Virginia Tech’s Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Center, the process begins when female adult mussels release strings of larvae, called glochidia, into the water. Designed by evolution to lure fish closer by looking like food, these packets of larval mussels attach themselves to the gills of fish introduced to the tanks. In the wild, that process would provide the glochidia a way to migrate upstream against the current before detaching to start their lives as filter feeders. In the tanks, the same strange method means that a threatened species will see a boost in its population.

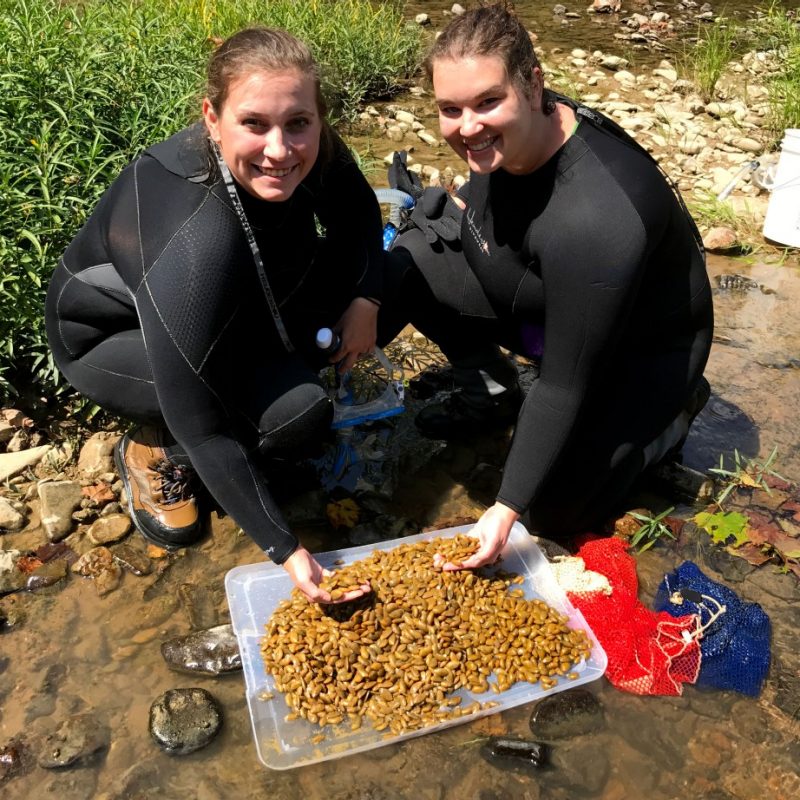

“We’re doing recovery work with a lot of endangered mussel species, which includes hatching them in our labs and then distributing them into water systems where there is a restoration need,” said Jess Jones, a restoration biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and an associate professor in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation. “In any given year we work with eight to 12 species, and we’ll release 10,000 to 20,000 animals into water systems in Virginia and the surrounding states.”

We give students a feel for work that is done in an applied context. In federal agencies, we think much more through the lens of trying to solve a specific problem, and our presence can help students realize that there are avenues outside of academia to pursue.

—Serena Ciparis

The process of transforming from larval mussels to juveniles takes 2-3 weeks, then the mussels detach and are collected by siphoning the bottoms of the tanks. The juveniles are brought to the mussel culture facility, where algae-laden pond water is cycled to feed them for 1-2 years, until they are large enough for release into ecosystems where mussel populations have declined due to environmental degradation or pollution.

This effort — critical in maintaining the health of freshwater ecosystems — is one of the many ways that the College of Natural Resources and Environment is partnering with federal agencies to serve Virginia and the nation while providing students with unique learning opportunities.

Cooperation between federal agencies and the university sparks innovation

Jones is one of several scientists in the college whose research and teaching is funded by federal agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Our federal partners benefit our students through their direction of research projects at both the undergraduate and graduate levels,” said Joel Snodgrass, head of the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation. “They provide examples and networking opportunities for students interested in employment with state and federal agencies, and they work closely with our faculty and other state partners to really amplify interdisciplinary science and its impacts on the citizens of Virginia.”

For federal scientists, having a connection to Virginia Tech means that they can utilize laboratory resources and cutting-edge technologies as well as collaborate with colleagues in natural resources and environmental conservation.

“The value added is tremendous on both sides,” explained Mark Ford, an associate professor of wildlife conservation and unit leader of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Virginia Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. “The university is getting talented faculty who are bringing important research questions to Virginia Tech not only for the commonwealth, but in some cases the nation. In return, instead of doing research in isolation, federal scientists can conduct their work amidst this ideas-generating campus.”

Ford has focused much of his recent research on endangered North American bats, which are crucial components of Virginia’s biodiversity and overall ecosystem integrity. “Endangered bats intersect not only forest management but the energy sector, development, and even defense,” he said. “Everyone who has to manipulate something on the landscape somehow bumps into challenges of bat conservation.”

This means that the Cooperative Research Unit, which has existed at Virginia Tech since 1935, works in collaboration with numerous federal and state agencies to address fish and wildlife management needs on just about every landscape imaginable, from pristine wilderness areas to urban centers.

To monitor bat populations, Ford’s team uses a noninvasive process of acoustic monitoring to “listen” to bats as they move through the landscape. The data reveal what bat species are populating an area and where they roost or hibernate for the winter, information that can help land managers better conserve and protect bat habitats.

The Cooperative Research Unit, which also includes Professor Paul Angermeier and Assistant Professor Elizabeth Hunter, currently supports 19 graduate students and four postdoctoral researchers in addition to cooperating with numerous other faculty and students, both within the college and across campus. The unit is currently researching an array of diverse subjects, from the efficacy of best land management practices in the upper Tennessee River basin to support aquatic health, to tracking the success of reintroduced elk in the coalfields of Southwest Virginia.

“We do a lot of work with the Department of Defense in collaboration with the college’s Conservation Management Institute,” added Ford. “The military installations in Virginia and elsewhere in the East are very actively managed, not only from a mission perspective but also from a natural resources stewardship perspective. As such, they are terrific places to acquire research data.”

Damage control

Other federal scientists are studying how to minimize human impacts on natural environments and how to restore landscapes that are damaged by pollution or recreational use.

Serena Ciparis, a contaminants biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and a research scientist at Virginia Tech, works with the Department of the Interior’s Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration program.

“We look at historically contaminated sites or contemporary spills and we figure out if there have been impacts to threatened or endangered species that are under the jurisdiction of our agency,” she said. “If there have been negative impacts, we figure out what they were and determine the economic cost required to restore that landscape.”

Ciparis, who teaches a first-year experience course introducing fish and wildlife conservation students to the pathways and programs available in the college, says that having government scientists on campus is a useful exposure to potential career trajectories.

“We give students a feel for work that is done in an applied context,” she explained. “In federal agencies, we think much more through the lens of trying to solve a specific problem, and our presence can help students realize that there are avenues outside of academia to pursue.”

Jeff Marion, a recreation ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Eastern Ecological Science Center and adjunct professor in the Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation, has been a trailblazing researcher on the ecological impacts of recreational activities in protected natural areas.

“I developed a program of research in the emerging field of recreation ecology,” explained Marion, who was a founding board member for the Leave No Trace educational program. “My work is focused on the management of visitors in protected natural areas, what the resource impacts from visitation are, and how, through science, we can better understand the influential factors so that impacts can be avoided or minimized.”

He echoes that the tangible quality of his work provides students with the chance to connect classroom learning with on-the-ground challenges.

“We’re trying to solve problems,” said Marion, who has done extensive research on the Appalachian Trail and is conducting research on the Pacific Crest Trail in Crater Lake National Park this summer. “The research that I do is very applied, very much about solving problems, and I think that’s true for all of the people who share my role at Virginia Tech.”

From student to scientist

The collaborations between university researchers and federal partners offer students a crucial transition from classroom learning to understanding how that learning translates into real-world contributions.

“It’s one thing for a student to be interested in fish conservation or biology and to choose that as a major,” Jones explained. “But then the question becomes, what does it mean to be a conservationist or a biologist? How does this learning translate into a job? What can you do in these fields?”

Having scientists like Jones and others on campus gives students crucial insights into career trajectories within federal and state agencies, an important steppingstone in bringing a new generation of natural resources scientists into the workforce.

“We are very fortunate to have a cadre of scientists representing several federal agencies working among us in the college,” said Paul Winistorfer, dean of the college. “Agency partnerships magnify our reach, synergize with our faculty and students, and broaden the impact of the work. I want to formally thank our partner agencies for their continued investment in the scientific staff at Virginia Tech.”