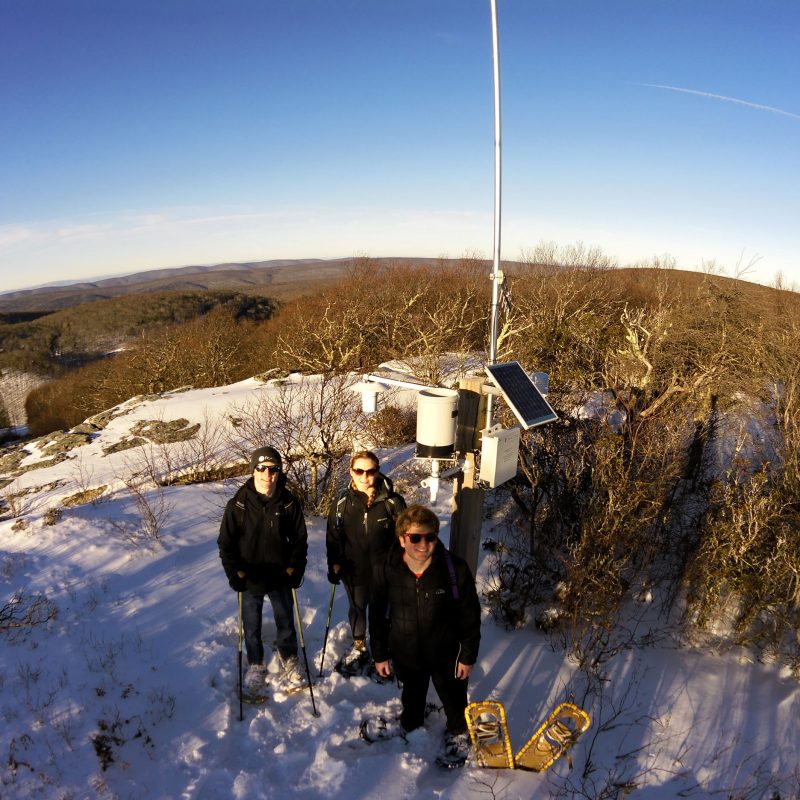

Meteorology faculty and students anchor weather stations on highest peaks in Virginia and West Virginia

August 15, 2019

Load your pack with power tools or a sledgehammer. Hike up Virginia’s highest peak. Get to work setting up and anchoring a weather monitoring station. Then maybe enjoy the view.

It’s just another day at the office for meteorology instructor Dave Carroll and his student volunteers, who have placed weather stations atop the highest mountains in Virginia and West Virginia to learn more about weather patterns at higher elevations.

“We are learning things we never knew before.”

The solar-powered, remotely accessed stations take readings every 10 minutes, collecting data such as temperature, wind speed, humidity, and rainfall, and then translate the data to a website, where visitors can learn the current conditions at Mt. Rogers or Bald Knob near Mountain Lake Resort in Virginia, or the five sites in West Virginia: Dolly Sods Wilderness, Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge (one on a peak and one in a valley), Bald Knob at Canaan Valley State Park, and Spruce Knob, the state’s highest peak, in the Monongahela National Forest. An additional station on campus is used for student training purposes.

Carroll is already seeing a return on investment: “It has been interesting to observe weather conditions on these high peaks over the last few years, especially those areas where few longer term observations have been taken. We are learning things we never knew before.”

One finding involves the temperatures on those peaks. Typically, the temperatures are comparable during times when a cold air mass is moving into the region. “However,” Carroll explained, “latitude quickly takes over and temperatures on Virginia’s rooftop warm significantly compared to those further north on Spruce Knob, where the cold air settles in for much longer periods. This effect is even noticeable between Mt. Rogers and Bald Knob outside of Blacksburg; Bald Knob stays colder for longer periods.”

“The winds have been very surprising, too — how long they blow and at such velocity,” added Carroll, who has observed winds blowing near 50 miles per hour for three days straight, and reaching 90 miles per hour during a 2018 nor’easter. Winds like these have toppled several stations and, along with a build-up of rime ice, snapped a tripod in two.

Carroll has learned how to adjust the methods and materials for anchoring the stations to account for the extreme conditions.

Despite the challenge of packing all of the equipment to each site — sometimes going where there are no trails — Carroll usually has plenty of volunteers. “Employers are looking for graduates with these skills in addition to the classroom-based science aspects of meteorology,” said Department of Geography Chair Tom Crawford, who adds that offering students hands-on instrumentation experience is an important part of the meteorology program.

Meteorology major Drew Shearer said, “I’ve learned more about the region and the difficulty in forecasting such a dynamic area.” He believes that having this kind of field experience and seeing how data is obtained will help him understand why he’s seeing certain kinds of data and make more accurate forecasts.

Fellow student Bradley Lamkin said, “This was an amazing experience! Installing the components helped me understand the data I was receiving from live reports.” He did, however, share a downside to the experience — the weather. “The most challenging part was dealing with the harsh conditions at the summits. When we installed the station on Mt. Rogers, the temperature was in the mid-20s, and the winds were gusting up to 50 miles per hour.”

Crawford added, “What Dave and his students have been able to do is really impressive. He has been building this monitoring network incrementally over the past several years, and it collects data for areas in Appalachia that aren’t well covered by other monitoring systems.”

Carroll echoed these thoughts and said of his aims for the ongoing project: “We want to fill in the data gaps for the National Weather Service. If they can get data from some of these places, it can be vital to them to know what’s happening out there.” It’s also vital for saving lives. In spring 2018, thanks to rainfall data from Bald Knob near Blacksburg, the National Weather Service was able to issue an emergency flash flood warning.

Eventually, Carroll would like to have a dozen weather monitoring stations in place throughout the highest elevations in Virginia and the neighboring states, but this may take some time as the process for obtaining permits for placement on state and federal lands can be lengthy.

In the meantime, the winds continue to blow and the data continues to stream in.