Re-creating a tornado in 3-D provides a more effective way to study storms

May 15, 2015

When meteorologist Jim Cantore from The Weather Channel stepped into the middle of an EF5 tornado re-created in 3-D in a four-story immersive installation at Virginia Tech, his perspective was that of someone 7,000 feet tall. Beneath him was the landscape of Moore, Oklahoma. Around him was the storm that killed 24 people in May 2013.

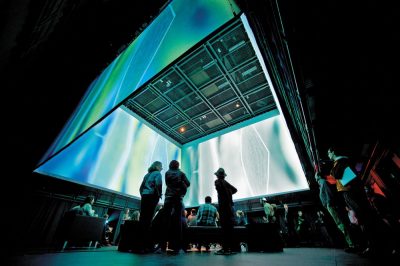

With support from Virginia Tech’s Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology, a student and faculty team from the Department of Geography and the Center for Geospatial Information Technology (CGIT) created the storm in the Moss Arts Center facility known as the Cube — a highly adaptable space for research and experimentation in immersive environments.

Cantore was tipped off by alum Kathryn Prociv (’11 B.A., ’12 M.S. geography), who is now a producer at The Weather Channel. She had been a storm chaser with the Virginia Tech team for three years and completed her master’s degree research on the effects of changes in land surfaces on rotating storm intensity in the Appalachian Mountain region.

When Prociv asked her former instructor Dave Carroll what was happening at her alma mater, he told her about the tornado re-creation in the Cube. She shared the news with Cantore, who promptly made arrangements to visit, accompanied by Dr. Greg Forbes, The Weather Channel’s severe weather expert. Winter storms delayed the visit a few months, but on Feb. 6 Cantore and Forbes were immersed in the re-created storm and broadcasting live.

The project was born when Bill Carstensen, head of the geography department, told Benjamin Knapp, director of the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology, about Carroll’s 3-D images of storms.

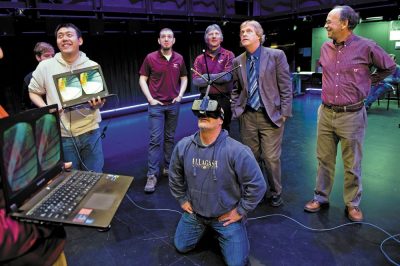

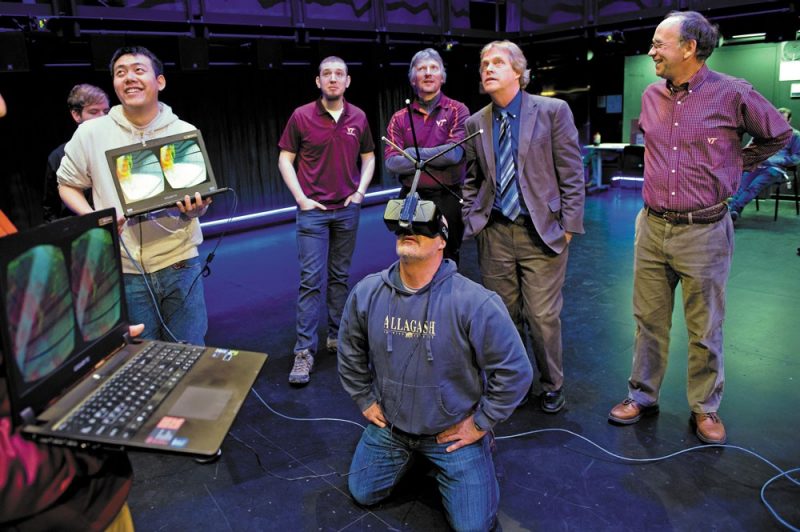

“We could build a tornado in the Cube,” Carstensen told Knapp during intermission at an event at the Moss Arts Center. Knapp urged him to write a proposal. Subsequently, a $25,000 Science, Engineering, Art, and Design grant from the institute made it possible to hire Matt Vaughan, a researcher from CGIT; Kenyon Gladu, a junior majoring in meteorology; and Trevor White, a master’s student in geography. Vaughan developed GIS map layers, Gladu worked with radar data, and White did the programming to retrieve the needed NEXRAD (Next-Generation Radar) data and render it appropriately. Institute staffer Run Yu, a computer science doctoral student, placed the storm in the Cube.

“We decided to produce that tornadic supercell because it was a catastrophic event,” said Carroll, who was south of Moore with the Virginia Tech storm chase team at the time the tornado occurred. The team members can often safely position themselves within a mile of a storm, but not in that instance. “It formed in the suburbs of Oklahoma City,” he said. “We couldn’t engage the storm because of the hazards in that environment — traffic, people fleeing. We had to back off.”

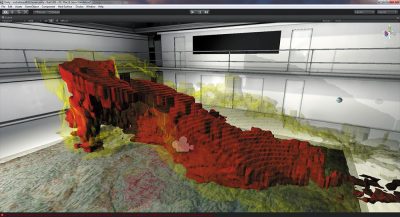

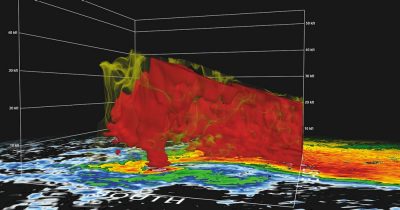

“People on the ground could not observe that storm from all angles and directions,” said Carstensen. “But NEXRAD radar captured data throughout the storm. It provided hundreds of thousands of data points in 3-D with several attributes at each data point, including the intensity of precipitation and the direction and speed of floating particulates.

“Our meteorology degree program ties geospatial science with weather data to meld atmospheric data with ground data. Geospatial science can register ground data — the rolling hills of Oklahoma and the land cover, such as agriculture, prairie, forests, and urban development. So in this re-creation of the Moore storm, there is the land cover on the ground and the storm above in perfect position.”

The Cube allows complete tracking of where a subject is standing, moving, and looking. An Oculus head-mounted display provides an image of what the subject would see from any vantage point. If there are two people in the Cube, they see each other as avatars and can see different points of view and exchange information. “Eventually, you will be able to zoom in, to control the scale of what you see,” said Carstensen.

“It’s like a video game environment in which you are embedded in the computer,” explained Carroll. “You can then study storms from different perspectives than in the field. You can peel away the outer layers of rain so you can see the business end of the storm. It is a more effective way of looking at storm structure.”

“It will be a valuable tool for researchers, forecasters, and students,” added Carstensen.

The ultimate goal is to bring real-time radar into the Cube — “real time” in this case being only a four- or five-minute delay. Carstensen and Carroll are working with Mike Kleist, a Virginia Tech mathematics graduate who is now vice president of engineering at Weather Services International (WSI), a weather graphics software company. “Mike said real time was absolutely doable,” said Carstensen. “We could visualize the whole East Coast, or any place that has been mapped, overlain by a snow storm or a storm surge model.”

“Combined with GIS information,” said Carroll, “this immersive technology could be extremely valuable for forecasters when alerting the public and for emergency managers when directing resources during life-threatening weather situations.”

Related Links

The Cube opens doors for discovery

To Benjamin Knapp, a rendering of an EF5 tornado in 3-D and surround sound in the Moss Arts Center’s immersive Cube is exciting.