All for the birds: Mitchell Byrd remains a friend of the college

August 15, 2014

At 86, alumnus Mitchell Byrd has lost neither his eagle-spotting ability nor his passion for birds. The aptly named Byrd still boards a private plane for annual eagle-sighting flights over the James and Rappahannock rivers, as he has for the past 38 years.

The plane cruises at an altitude of about 300 feet, sometimes slowing down to 80 mph for a better view. Byrd describes it as “living on the edge” and wonders how much longer he’ll be able to make the flights. The information he gathers is used to predict future eagle habitat and is shared with land planners in the hope that key roosting areas will be sheltered from development.

In 1976, only 33 bald eagle nests remained in Virginia, none of them along the James. The federal government appointed Byrd to lead the Chesapeake Bay Bald Eagle Recovery Team, and soon the College of William and Mary professor was busily tracking eagles and speaking out to save their nesting areas. Byrd took influential people to see some of the wild areas eagles frequented — habitat now protected as the 4,200-acre James River National Wildlife Refuge.

These days, more than 600 eagle pairs tend nests in Virginia, and the James River supports the largest summer eagle population in the eastern United States. Byrd attributes the eagles’ comeback to a federal ban on the use of the pesticide DDT as well as Endangered Species Act protection, but others say Byrd’s surveys drew attention to previously unknown eagle habitat, which helped authorities protect nesting grounds.

“I don’t think the refuge would be there if not for Mitchell,” said Jim Fraser, Virginia Tech wildlife professor and recipient of the 2013 Mitchell A. Byrd Award from the Virginia Society of Ornithology, who was drawn into bald eagle research by Byrd in the 1990s.

After receiving his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate from Virginia Tech, Byrd joined the faculty of the College of William and Mary in 1956, eventually becoming chairman of the biology department, leading it to national recognition. He later founded the Center for Conservation Biology before retiring in 1994. Over the years, the chancellor professor emeritus and director emeritus, who remains active at the center, has worked with almost every species of bird found in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

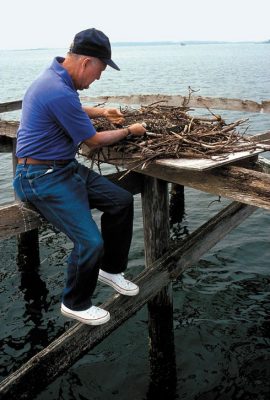

Leading the Eastern Peregrine Falcon Recovery Team, Byrd took up hammer and nails to help build towers to serve as nesting areas for some 240 peregrine falcon chicks being reintroduced to the Chesapeake coastal area. The birds had been almost completely exterminated in Virginia by pesticide poisoning — down to a single breeding pair in 1981 — but today the breeding population is close to 40.

Byrd also built osprey nesting platforms, tagged at least 3,500 osprey, and worked to protect rare woodpeckers, but he will always be best known for his work with eagles. In 2007, he received the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Recovery Champions Award for his monitoring, research, and protection of the Chesapeake Bay bald eagle population.

Surprisingly, much of Byrd’s early work at Virginia Tech was not on birds, but on muskrats. Byrd spent much of his time on Stroubles Creek below the Duck Pond, conducting thesis research on the muskrat population there. Occasionally, he trapped a few for dinner with his master’s advisor, a fan of fresh muskrat.

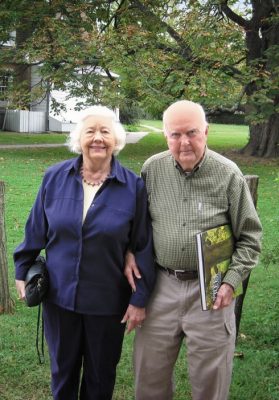

As longtime supporters of the college, Byrd and his wife, Lois, received the Friends of the College award in 2008. Their generosity includes three charitable gift annuities supporting the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation and gift plans to provide department faculty support in the area of conservation biology.

“I have always appreciated my education at Virginia Tech,” Byrd said. “Lois and I respect the value of a quality education. We are pleased to be able to give back to this outstanding college.”

Dean Paul Winistorfer acknowledges the Byrds’ support. “I am always so genuinely impressed when someone with such academic and career scientific success also gives back so generously,” he said. “Mitchell and Lois Byrd have been generous donors and actively involved with the college, and we deeply appreciate their kindness.”