One Man's Trash is Another Man's Building Material

August 15, 2011

Reduce. Reuse. Recycle. In today’s society, people are being urged more and more to follow these principles. Despite advances in sustainability practices and the increasing number of recycling programs, piles of trash get dumped in landfills every day. Litter clogs up ditches and lines streets and highways. Sometimes it seems like whole towns could be built out of the items we throw away. What if there were another way to solve this problem? What if it were actually possible to create buildings out of trash? Thanks to the efforts of the nonprofit organization Long Way Home (LWH), these what-ifs are being turned into realities.

Lars Battle, a student in the Master of Natural Resources program at the National Capital Region campus in Falls Church, Va., is working with LWH on projects in Guatemala, where he had served as a Peace Corps volunteer in 2002. In a predominantly indigenous municipality in the country’s northwestern highlands, he helped organize community development councils at the village level and was invited to join the board of directors of LWH in 2007. “The goals of our organization are to break the cycle of poverty through a community development strategy that brings local residents, particularly youth, together to learn about ecofriendly living, appropriate sustainable technologies, and improved waste management solutions,” he explained.

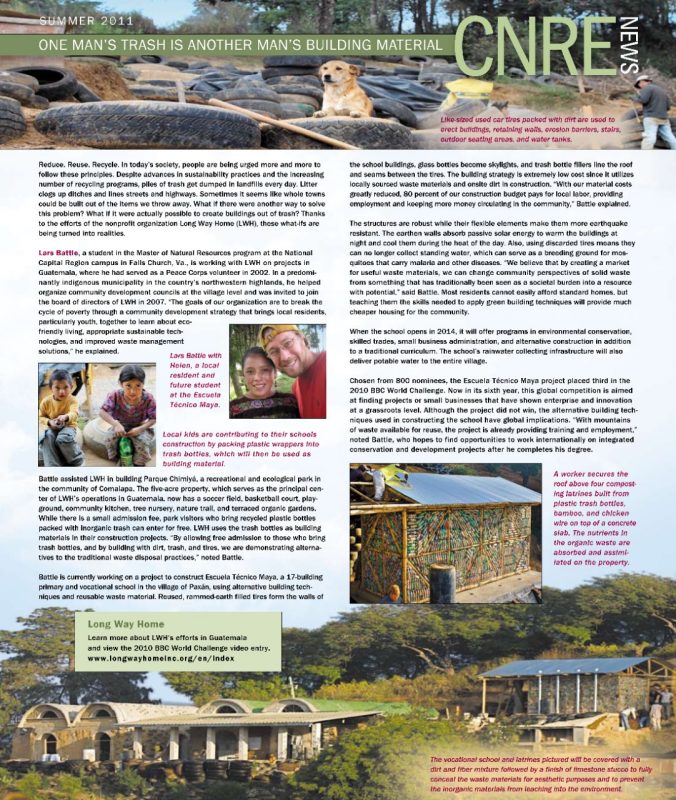

Battle assisted LWH in building Parque Chimiyá, a recreational and ecological park in the community of Comalapa. The five-acre property, which serves as the principal center of LWH’s operations in Guatemala, now has a soccer field, basketball court, playground, community kitchen, tree nursery, nature trail, and terraced organic gardens. While there is a small admission fee, park visitors who bring recycled plastic bottles packed with inorganic trash can enter for free. LWH uses the trash bottles as building materials in their construction projects. “By allowing free admission to those who bring trash bottles, and by building with dirt, trash, and tires, we are demonstrating alternatives to the traditional waste disposal practices,” noted Battle.

Battle is currently working on a project to construct Escuela Técnico Maya, a 17-building primary and vocational school in the village of Paxán, using alternative building techniques and reusable waste material. Reused, rammed-earth filled tires form the walls of the school buildings, glass bottles become skylights, and trash bottle fillers line the roof and seams between the tires. The building strategy is extremely low cost since it utilizes locally sourced waste materials and onsite dirt in construction. “With our material costs greatly reduced, 80 percent of our construction budget pays for local labor, providing employment and keeping more money circulating in the community,” Battle explained.

The structures are robust while their flexible elements make them more earthquake resistant. The earthen walls absorb passive solar energy to warm the buildings at night and cool them during the heat of the day. Also, using discarded tires means they can no longer collect standing water, which can serve as a breeding ground for mosquitoes that carry malaria and other diseases. “We believe that by creating a market for useful waste materials, we can change community perspectives of solid waste from something that has traditionally been seen as a societal burden into a resource with potential,” said Battle. Most residents cannot easily afford standard homes, but teaching them the skills needed to apply green building techniques will provide much cheaper housing for the community.

When the school opens in 2014, it will offer programs in environmental conservation, skilled trades, small business administration, and alternative construction in addition to a traditional curriculum. The school’s rainwater collecting infrastructure will also deliver potable water to the entire village.

Chosen from 800 nominees, the Escuela Técnico Maya project placed third in the 2010 BBC World Challenge. Now in its sixth year, this global competition is aimed at finding projects or small businesses that have shown enterprise and innovation at a grassroots level. Although the project did not win, the alternative building techniques used in constructing the school have global implications. “With mountains of waste available for reuse, the project is already providing training and employment,” noted Battle, who hopes to find opportunities to work internationally on integrated conservation and development projects after he completes his degree.