Formaldehyde emissions challenge wood-based composites industry

May 15, 2017

Wood-based composites are used to make American homes and many of the wood-based items in them. These composites, often made from wood fibers, chips, and flakes, are versatile and useful, and they make timber resources more sustainable.

“Composites make it possible to use lower quality wood, reduce waste, and even extend the impact of high-quality timber,” said Professor Chip Frazier of the Department of Sustainable Biomaterials and director of the Wood-Based Composites Center. “Fossil fuel-based adhesives make this green technology possible for consumers and society.”

Composites require a strong adhesive to hold everything together. The most popular adhesive, because it is effective and cheap, contains formaldehyde, which is derived from natural gas. Formaldehyde is critical to the production of wood composites because it creates molecular networks that bind particles of wood together for the life of the product. “However, in certain cases, water in the atmosphere can reverse this reaction, causing formaldehyde release into the indoor air,” Frazier said. “And this is a potential problem for us all. When formaldehyde levels are too high, they can be toxic to humans.”

For decades the federal government has set limits for allowable formaldehyde emissions from nonstructural composite products like particleboard. However, the Formaldehyde Standards for Composite Wood Products Act, signed into law in July 2010, required even stricter emissions restrictions down to levels that are very near the natural emission of wood itself.

Lignin, the natural polymer in wood that allows trees to stand tall, creates formaldehyde. Frazier calls this “biogenic” formaldehyde, while that created from natural gas and used in adhesives is termed “synthetic” formaldehyde. “Regulators and even some scientists did not realize that wood releases biogenic formaldehyde, particularly when wood is heated, which is how composites are made,” he said.

The new emission limits are so low that industry must now account for biogenic formaldehyde, and the industry members of the Wood-Based Composites Center asked Frazier’s research group to improve the understanding of how wood produces formaldehyde.

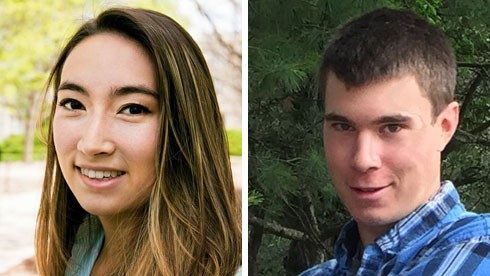

Frazier’s research group included several students. Guigui Wan led the effort, assisted by Mohammad Tasooji; both were doctoral students macromolecular science and engineering, an interdisciplinary degree program spanning multiple departments and colleges. Also conducting research in summer 2015 were Heather Wise, who received her bachelor’s degree in sustainable biomaterials in December 2015, and George Lewis, a 2016 graduate in materials science engineering in the College of Engineering.

“We study the chemistry of how wood forms formaldehyde and what problems this poses in meeting the federal standards,” Frazier explained. “Heather and George helped demonstrate that living trees contain biogenic formaldehyde and at vastly different levels among three different tree species.”

Lewis sampled cores from yellow-poplar trees on campus, and Wise, now a master’s student at the University of Washington, sampled Virginia pines in the woods just outside Blacksburg. Wan and Tasooji worked on these tree species plus radiata pine trees from a Chilean plantation.

Tasooji developed a microscale method to extract and quantify biogenic formaldehyde from a large number of living trees without killing or damaging them. Using this method, the team was able to measure formaldehyde levels in tree increment borings before and after drying and heating. As expected, heating significantly increases the production of formaldehyde — tenfold to thirtyfold.

As far as consumers are concerned, there is no difference between synthetic and biogenic formaldehyde; all that matters is if the level is too high. But, Frazier explained, “Biogenic and synthetic formaldehyde are different at the atomic level. It’s feasible for us to distinguish the two because of differences in nuclear isotope ratios.”

Currently, Frazier and colleague Brian Strahm, associate professor in the college’s Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation, are continuing this research at the request of the center’s industry members. Strahm, an expert in using stable isotopes to reveal ecological processes, said, “Chip has grabbed my attention because he wants to show if any of the formaldehyde emitted from wood composites has a natural origin.”

Frazier hopes that his work with Strahm can help determine new ways to reduce formaldehyde emissions in American homes. According to Frazier, “Using a different adhesive would be very costly to the average American.”