New Meteorology Major Generates a Storm of Interest

November 15, 2011

Although the meteorology major in the college’s geography department is only weeks old, student interest has been swirling like a cyclone since July 2011, when the State Council for Higher Education in Virginia approved the new bachelor of science degree program to begin in January 2012. Many students have expressed interest in the program and more than 30 have switched to the new major, the first meteorology degree offered in the state. Six of those students are already on track to graduate in May. “There’s a lot of pent-up demand,” said Bill Carstensen, department head. “Many geography majors are becoming meteorology majors.”

Geography students who are in the geospatial and environmental analysis option meet many of the requirements for the meteorology degree, but with the addition of new courses offered in the 2011-12 academic year, the curriculum now meets guidelines developed by the American Meteorological Society and the National Weather Service. Associate Professor Andrew Ellis was recruited from Arizona State University to teach the new courses; his expertise in meteorology and climatology complements the strengths of the department’s faculty.

Other students are coming into meteorology from a variety of fields — engineering, physics, crop and soil environmental sciences, chemistry, math, computer science, even theatre. Some are adding meteorology as a second major, according to Carstensen.

The timing couldn’t be better for student Dan Goff, who came to Virginia Tech knowing he wanted to be a meteorologist. Goff is the chief meteorologist at Virginia Tech’s WUVT-FM radio station and also blogs and tweets as “Weather Dan” in the Richmond area (see related story). “I was hoping the program would be here before I graduate,” Goff said. “Now I’ll be able to leave Tech in May 2013 with degrees in both meteorology and geography.”

The new major plays to Virginia Tech’s existing strength in geospatial information technology, which incorporates geographic information systems (GIS) and remote sensing, and combines it with classical meteorology examining the physics of the atmosphere. While most other programs look primarily at atmospheric patterns, geospatial technology allows students to consider how landforms affect weather patterns. In this relatively new area

of research, students learn to predict severe weather and to model and assess its impacts on landscape features and the human environment. “We look at what goes on in the atmosphere and on the ground,” said Carstensen. “We take the geospatial aspect further than any other university meteorology program.”

Graduate student Kathryn Prociv is studying the effect of Appalachian topography on tornadic thunderstorms, including the one that hit nearby Pulaski County in April 2011. In her research, which involves correlating terrain with radar data to figure out how topography influences the low-level winds of thunderstorms, she uses GIS and remote sensing to look at a meteorological problem. Like Prociv’s research, the new degree program has an interdisciplinary focus in geography. “Students graduating will have not only meteorology knowledge but also a skill set in geography,” said instructor Dave Carroll. “That will hopefully make them very attractive candidates for graduate school and employment.”

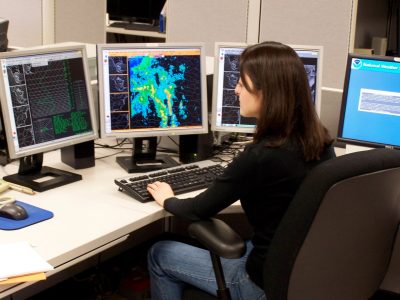

The university’s close proximity to the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Blacksburg is another asset to the program. Students can apply what they learn in the classroom to real-world forecasting experiences through internships at the office.

Carroll’s Hokie Storm Chase course offers another hands-on experience operating weather equipment. The meteoric rise in popularity over the past decade of the course’s annual trips to track storms across the Great Plains spurred the department’s interest in creating the meteorology major.

For graduates of the new program, the combination of skills will open doors for employment with a host of federal and state agencies, as well as private weather forecasting companies, such as AccuWeather. Meteorologists also work for the military, commercial airlines, and other transportation companies, as well as news organizations and other agencies.

“Our degree program adds human and physical geography and remote sensing to the meteorology mix,” Carstensen said. “We predict not only the weather, but what effect it will have — and that’s important.”